At the beginning of February, we were finally able to light a fire after it had rained a decent amount, over 50 mm. Before that, making fires was generally prohibited because the extreme drought had increased the risk of forest fires.

Beforehand, however, we had already dug the hole for our biochar project: 1.5 m in diameter and 1 m deep in a funnel shape that was considered ideal for the production of biochar. This shape was called Kon Tiki by the developers. The volume of our hole is approximately 0.4 m³. The optimum size is 2 m in diameter and 1.5 m deep.

At the beginning of December, we learned how to produce biochar at a special seminar in Seville. Up until then, we had only experimented with small quantities using an old barrel and even with three barrels, but the amount of biochar produced was far too small for our needs. So we decided to move into a larger scale of biochar production. However, this also requires more material to burn.

Basically, we have enough material, or rather enough material accumulates on our property every year. But until now we have always chopped it up. Using the tree cuttings in a new way means we have to work differently: now, we divide the material into different sizes: firewood (starting at 8 cm diameter), chippings (3 to 8 cm diameter) and biochar (up to 3 cm diameter). Since the authorities restrict fire-making to the period from October to the end of April, we can chop all material produced from May to September.

The optimum charcoal is not produced until a temperature of 500°C is reached, and, very importantly, the combustion must take place in the absence of oxygen, a process called pyrolysis. The funnel shape of the hole favours this special type of combustion, as the gases produced then circulate in the hole in a special way, thus making the high temperature possible through the combustion of these gases. It is also important that the fire is always covered by flames so that no oxygen can penetrate.

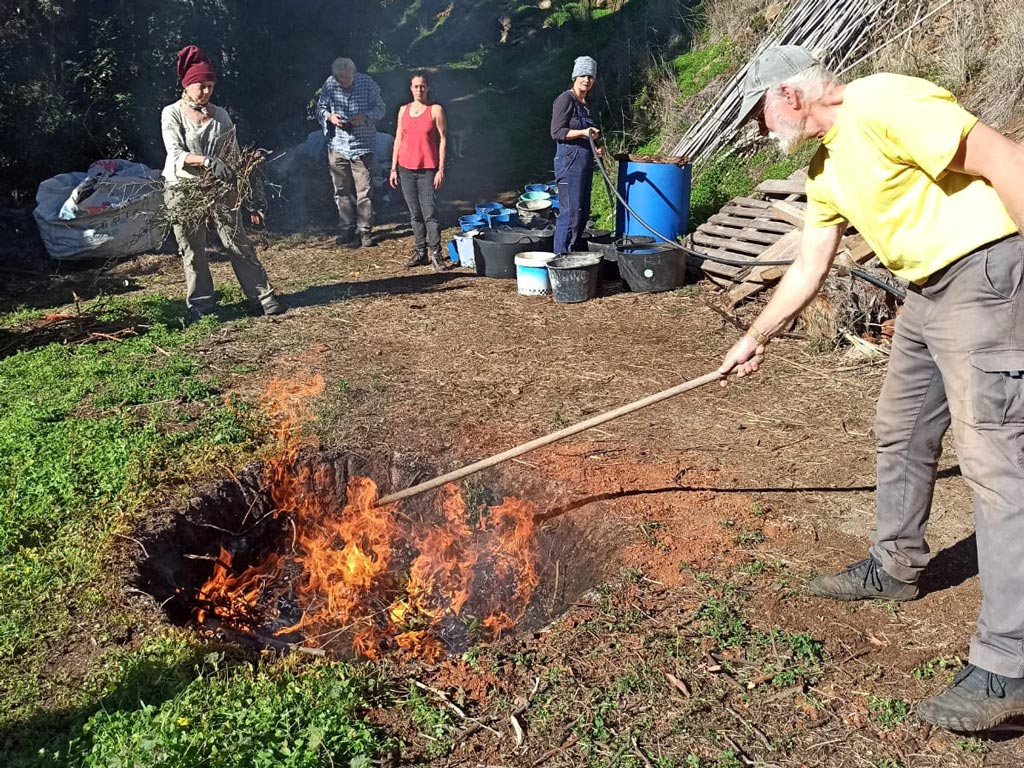

Once we had piled up the bushes and wood to be burned around the hole, in a safety distance of three meters from the fire, we were ready to start. But first, we filled many buckets with water to extinguish the fire later. A lot of friends joined us for this premiere and we all took turns adding small amounts of combustible material to the fire. Leaves that had become wet from the recent rain turned out to be unsuitable, but there was plenty of other material. We had to keep checking the direction in which the flames were burning and where new fuel was needed for the fire, all of which meant we were busy keeping the fire burning and directing the burning process in the right way. After about two hours, the hole was completely full and the final act could begin.

The burning process must be stopped abruptly and thoroughly so that the fire does not continue to burn inside; otherwise the wood burns to ash instead of charring. The hole in the ground is not a watertight container and the water that flows in naturally seeps directly into the ground. So it wasn’t clear exactly how much water we would need to fill the hole and extinguish the fire. To do this, we then placed the many buckets filled with water around the hole – at an appropriate distance, of course. At a signal, the buckets were then emptied into the fire as quickly as possible, immediately filled with water again and the water emptied into the fire once more, and so on until the water level in the hole was visible and the top layer of coal rose, i.e. floated on the water. The whole thing went much faster than we had expected, and after we had used about 350 litres of water, the hole was full of water and the fire extinguished. There was a lot of hissing, but very little steam.

As soon as the coal had cooled down to the point where it was safe to touch, we checked the quality. Larger pieces could be easily broken up and crushed further. This showed us that the coal was of good quality. The water level gradually sank and now everyone could still feel the warmth from the fire with their hands in the damp coal and hold, smell and feel the freshly produced coal.

The next day, we took the finished coal out of the hole and let it dry on plastic sheets. It was then collected, spread out again on a concrete surface and allowed to dry further. After a few days, we crushed it by walking over it and twisting it back and forth with our feet. It was then sieved and filled into sacks. This resulted in approx. 350 litres of biochar. As we need at least 1 m³ of charcoal per year, we will repeat this action as soon as we have collected enough combustible material.

It was a great experience to produce biochar together and also to transform the tree cuttings into a new, special form that contributes to improving the soil in a variety of ways. In addition, biochar fixes carbon in the soil, which in turn has a positive effect on the climate balance. By doing this, we can increase soil fertility and do something for the climate at the same time.